Inequality is a workplace hazard and, like RSI and bad backs, gendered violence can be prevented. The CEO of Our Watch, Mary Barry, explains how workplaces can help create a future that's free of violence against women.

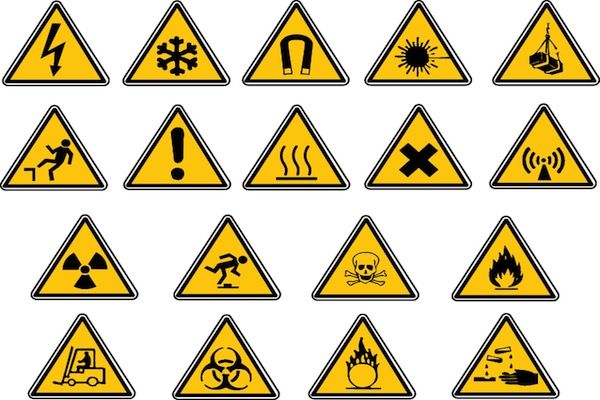

Hard hats and boots or rape and sexual harassment. Which of these says Occupational Health and Safety to you? When we think of workplace safety we’ve been conditioned to concentrate more on ‘lifting from the knees’ than gendered violence and it is about time that changed.

Last week Fairfax Media released its investigation into sexual harassment in the workplace. The organisation spoke to women across a broad range of roles which revealed many are verbally or physically harassed on a daily or weekly basis. Rape threats and physical attacks were less common but still happened once a year for some.

The week before, the Victorian Trades Hall Council released a report indicating gendered violence is a serious health and safety problem for many Victorian workers.

More than 60% of the 500 women surveyed experienced bullying, harassment or violence in their workplace and felt at risk. Nearly a quarter said that they weren’t treated with respect at work.

Let’s look back a hundred years to a time when workplace health and safety wasn’t a priority. Unsafe industrial machinery coupled with a lack of basic safety procedures meant that workers were vulnerable to serious injury and death.

These days, employers take their duty to prevent injury and illness seriously. This includes psychological harm, such as bullying, which is covered in Occupational Health and Safety legislation.

The 1984 Sex Discrimination Act holds employers legally responsible for sexual harassment unless they’ve taken reasonable steps to prevent it. In Victoria, the Equal Opportunity Act 2010, requires employers to take reasonable and proportionate measures to prevent sexual harassment and discrimination on the basis of gender.

Unfortunately, regulatory frameworks aren’t sufficient alone. These new reports, along with many others, make it clear that many women continue to live in fear of violence and harassment at work. In the same way that we ensure our actions don’t endanger our colleagues, we need to ask what we can put in place to help individuals prevent gendered violence. In other words, what’s the behavioural equivalent of a fire drill?

To those who say that work is not the place for promoting equality, that gendered violence does not exist; we say, just look at the statistics.

One in four Australian women has experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of a current or former partner. Approximately 75% of Australian women report experiencing unwelcome and unwanted sexual behaviour in the workplace. And Australian employers are losing $1.3 billion annually as a result of violence against women.

Violence against women affects workplaces in many costly ways: increasing absenteeism (employees not coming to work); increasing presenteeism (employees coming to work sick); increasing staff turnover and decreasing productivity. Survivors need time and support to attend court hearings, medical appointments and other services to help them escape violence.

And remember: perpetrators work too. The Victorian Trades Hall Council report says their attitudes and behaviours towards women may spill over in their workplaces, potentially posing a health and safety risk for colleagues.

Our Watch is currently leading a Workplace Equality and Respect project, funded by the Victorian Government, with four workplaces: La Trobe University, Connections UnitingCare, Carlton Football Club, and North Melbourne Football Club. These organisations are working with us to produce guidance for workplaces on key actions to prevent violence against women.

So what can workplaces do to reduce harassment and inequality? They can confront organisational practices that devalue, exclude or marginalise women and support increasing the number of female leaders.

What can individuals do? If someone makes a sexist comment or joke at work, say something. Report discrimination, harassment or violence to your manager or director. Look at your attitudes towards and expectations of women and men at work. Do you expect men and women to do different kinds of tasks, like assuming that female staff will organise all the social functions?

Harassment and gender inequality are affecting the health and safety of employees but prevention requires more than an Act or a hard hat. We need leaders to take action. We need individuals to take action.

If we do these things now, the workplaces of the future will have helped to create an Australia free of violence against women; an Australia where women are not only safe, but respected, valued and treated as equals in private, public and professional life.

Harassment and inequality should be treated like a workplace hazard by Mary Barry. Available from <http://www.womensagenda.com.au/talking-about/opinions/item/7550-harassment-and-inequality-should-be-treated-like-a-workplace-hazard> [Dec 08, 2016]